Dear Friends,

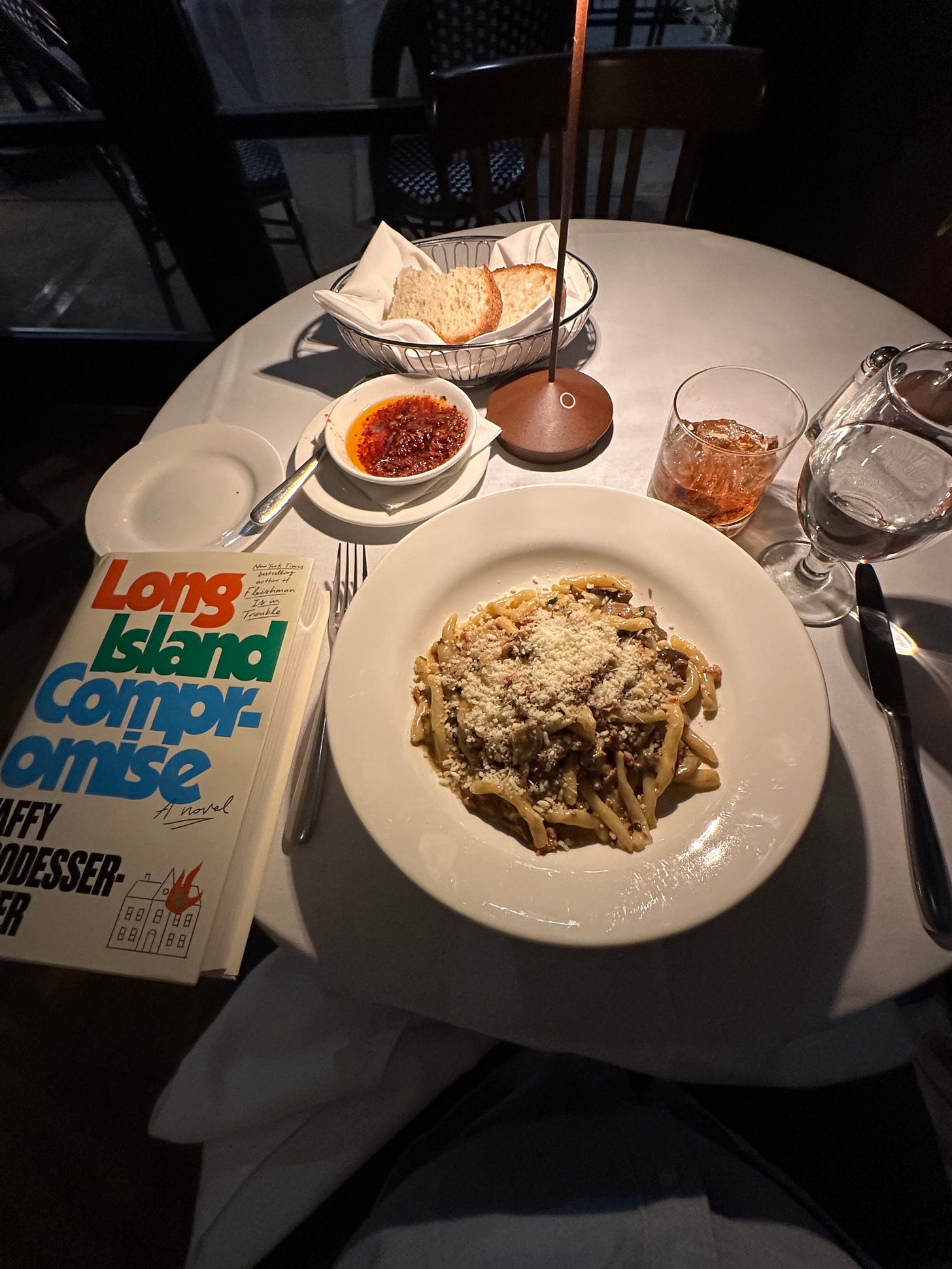

Welcome back to The Crunchwrap! I’m back in New York after a few weeks on the road. On Tuesday, I caught the release of (aspirational) friend of The Crunch Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s new novel, Long Island Compromise. It’s very good so far, so consider that a 60-page endorsement.

Two more endorsements: A friend had to bail on the reading, but I still went solo and strongly bless this move. Also – and this is probably one of the most obnoxious things I’ve ever written here – I can’t vouch enough for the restorative powers of dinner alone in an old, unfussy red sauce joint with a new book and a Carpano Antica on the rocks.

As I mentioned in the last ‘wrap, I’ll be steering some of these newsletters (metaphorically) toward the theme of social isolation in America, which is something I’ve been fixated on, at least as far back as the McDonald’s dining room.

Of course, I’m not alone in believing that a lot of our alienation (and political division) has to do with America’s work and productivity culture, which deprives us of downtime and makes moments not spent doing things feel or seem decadent or wasteful. This itch latches onto our go-it-alone social policies, which fail to give us support for time and resources that many in our peer nations tend to enjoy. Making everything worse is our rigid love affair with self-reliance, which fuels a collective stigma around needing help. Whew.

I’ll concede these heavy, high-level topics are better suited (cough cough) for a book than for a Taco Bell-themed newsletter, so I’ve also been trying to think of social isolation in terms of missed opportunities to connect.

As someone who shakes his head in disbelief at my phone’s weekly screen time alert, I know firsthand how technology can get in the way. To boot, in-person hangs have fallen out of favor….which is compounded by there being fewer places to go for idle time-wasting with friends or strangers.

So, at the risk of coming on strong, I’m working on being more proactive about socializing now that I’ve got more free time again. Last month, I traveled to the West Coast for a family wedding and some work, and I also managed to find time for four separate hangs with friends now living in the Bay Area. These weren’t all glamorous, heavy-lift affairs and they really couldn’t be. I was only free during the week and folks be busy. So I served as lunchmate during one friend’s workday in San Francisco. I drank a few glasses of seltzer with an old friend at his dining room table in Berkeley while we waited for his son to come home from day camp.

An unexpected highlight came on the morning before my flight, when I took a “run” down the Embarcadero. I ended up at Oracle Park, the stadium where San Francisco Giants play. And that’s when I stumbled upon a shrine to baseball great Willie Mays. Mays, who played for the Giants for over a decade after the team moved to San Francisco from New York in 1950s, died at age 93 the week before I arrived. And outside the stadium, a shrine to Mays had materialized.

NOW, for those unfamiliar with Willie Mays or whose eyes tend to glaze over1 at the very mention of baseball, please indulge me. Here’s how The Defector’s Ray Ratto nutshelled some of Mays’ legacy:

He was the best player in an era when nearly every team had a Hall of Famer in the regular lineup. Mays was there at the moment when talent replaced race as the sport’s prime directive, when even the most recalcitrant segregationist owners finally found the time and financial inclination to teach their scouts color blindness; when the sport finally became what it could be, Willie Mays was something very like the living fulfillment of that promise. He has the third-greatest career WAR [wins above replacement] among position players, behind only Babe Ruth and [Barry] Bonds, and that list would look different if he hadn't lost most of his second and all of his third seasons to the draft.

All of this background is to offer up that Mays’ life held different meanings for different people for different reasons. I already knew this, but seeing it on display made it resonate. Tributes, flowers, candles, letters, photos of Mays with fans had been blown up and set down.

I asked the stadium guard posted to keep order at the crowdsourced ofrenda if she knew why several people had left cans of Modelo for him and she admitted that she didn’t know, but guessed that it was because in his very long retirement, Mays was a fixture at area bars, where he almost certainly never had to pick up a tab. Maybe Modelo was his pick.

Regardless, he mixed easily with people despite his fame, she explained, and always said hello back to people who shouted Hey, Say Hey at him. And though the Giants had been on a road trip all week, people had been coming by the stadium to pay their respects to Mays.

I hung around for a bit, watching people line up for pictures and take in the curios at the shrine. I chatted with one fan who had trouble collecting himself as he told me that he used to see Mays play with his parents. I’ll never think of Mays or San Francisco the same.

Till next time,

Adam

or twitch in rage